To celebrate the artist’s newly-released collection of drawings, we chatted with her about her methods and inspiration.

Lolly-K-Pop, original ink, watercolour and acrylic on paper, 2021

Hang-Up: How did you first get interested in art?

Delphine Lebourgeios: I was more interested in literature and writing than art during my teens. Visual arts came later. After a year studying Art History and French Literature, I followed a friend who was taking the entry exam for the ENBAL (Fine Art School of Lyon) and I got selected. The conceptual approach of the school made me realise that there were no limits to what could be done. There was a realm of possibilities. Anything could be Art.

HU: Who inspired you at the time?

DL: My work was mostly photography-based in Lyon, and Cindy Sherman, Sophie Calle, Pipilotti Rist and Rebecca Horn were revelations. In the last year of my BA, I travelled to Vietnam for six months and that’s when I started drawing. Photography was analogue at the time and required a long process for which I wasn’t equipped out there. There were a lot of crazy things happening around me and I needed the immediacy of drawing to document them, so I started a drawing diary.

Two Girls, Ink on Chinese rice paper, 2021

HU: What materials do you use in your work?

DL: I work with ink and watercolour on different papers. I love paper because it has an ephemeral and fragile quality. I have started to use Japanese papers for my B&W sketches. I like the lightness and transparency of these, the preciousness too. They are very delicate…

HU: Your work only features women. Why?

DL: It’s not a conscious decision to only draw women …. at the moment it’s what feels right. I’m particularly interested in female emancipation and group dynamics.

HU: Your latest work focuses on the notion of female hysteria. How did you get interested in that, and did you have to do a lot of research?

DL: A couple of years ago, I started reading articles about Charcot at the Salpetriere hospital in Paris, and the effects his work had on culture and art at the time. In the 19th-century, Charcot exhibited “hysterics” in fabricated performances to an all-male audience of writers and artists, in order to document his research. The famous photographs and drawings of “youthful hysterics” provided cultural materials for many artists (including the Surrealists, Dali, Rodin, Degas etc…).

What triggered me is the blatant misogyny in some of the artworks and in Charcot’s studies. One can argue that hysteria is a first feminist attempt at shutting down patriarchy, but these young women were often attractive subjects for the male voyeuristic gaze, their convulsing positions revealing more flesh than what was considered acceptable in those days. The most famous “hysterics” were also the prettiest ones. The women’s distress was exploited to provide entertainment value, which made them even more vulnerable.

I was also interested in the fact that “Hysteria” belonged to Charcot’s era, and was later dropped as a medical diagnosis. It’s as if the condition disappeared in a puff of smoke after Charcot’s antics.

After a lot of reading on the subject, I then moved on to exploring adolescence: Teenage girls are specifically associated with hysteria. There’s something that fascinates me in the intensity of emotions that goes into fandom or conversion disorders (when people exhibit symptoms affecting the nervous system that cannot be explained by physical illness or injury) – girls screaming in frenzy. There’s a power in irrationality, like a visionary trance of some sort.

HU: What does feminism mean to you?

DL: I’m still trying to figure this out… Feminism has many voices today and some resonate more than others. In the art world, although things have improved, it's still much harder for a woman to gain visibility and recognition.

As a kid I wanted to be a boy. Boys were allowed to do more stuff, and they seemed to have greater importance. I spent all my holidays at my grandparents house in rural France and was fascinated by the shed, which housed an array of mysterious tools. I wasn’t really allowed or encouraged to use them or build anything with them, but my male cousin was. He and my Granddad crafted beautiful wooden objects with these tools: a small blue painted boat, a miniature windmill, a plane with a metallic propeller… I was in awe of my cousin but this difference of treatment left me feeling inadequate and envious. It predetermined a rebellion.

At art school, my work was also unconsciously feminist even if the word was never mentioned. Most tutors were older men and I felt disruptive… In first year, I took a series of photographs where you could see me waxing my upper lip, peeing with a bloody sanitary towel, showing pit hair. These were provocative and deliberately not “pretty”. They failed to impress at the time, but a woman tutor saved me from being expelled.

Now, for me, it’s about being able to do what I choose and with the same chances and opportunities as a man. Being independent is also crucial.

HU: What's your favourite place to exhibit?

DL: I've really enjoyed showing at The Other Art Fair in Brooklyn a couple of years ago and of course the opening of Hang-up's new gallery was fantastic. I’m also interested in creating a site specific project at some point soon. I like the idea of images outdoors, in the wild.

HU: What are you working on now... and what's next?

DL: I’m preparing a limited edition print as part of the “All Hysterical” series and then we'll see…

Delphine Lebourgeois has created seven new drawings as a continuation of her brilliantly-received All Hysterical series. See them on the artist's catalogue.

More from Artists

Artists

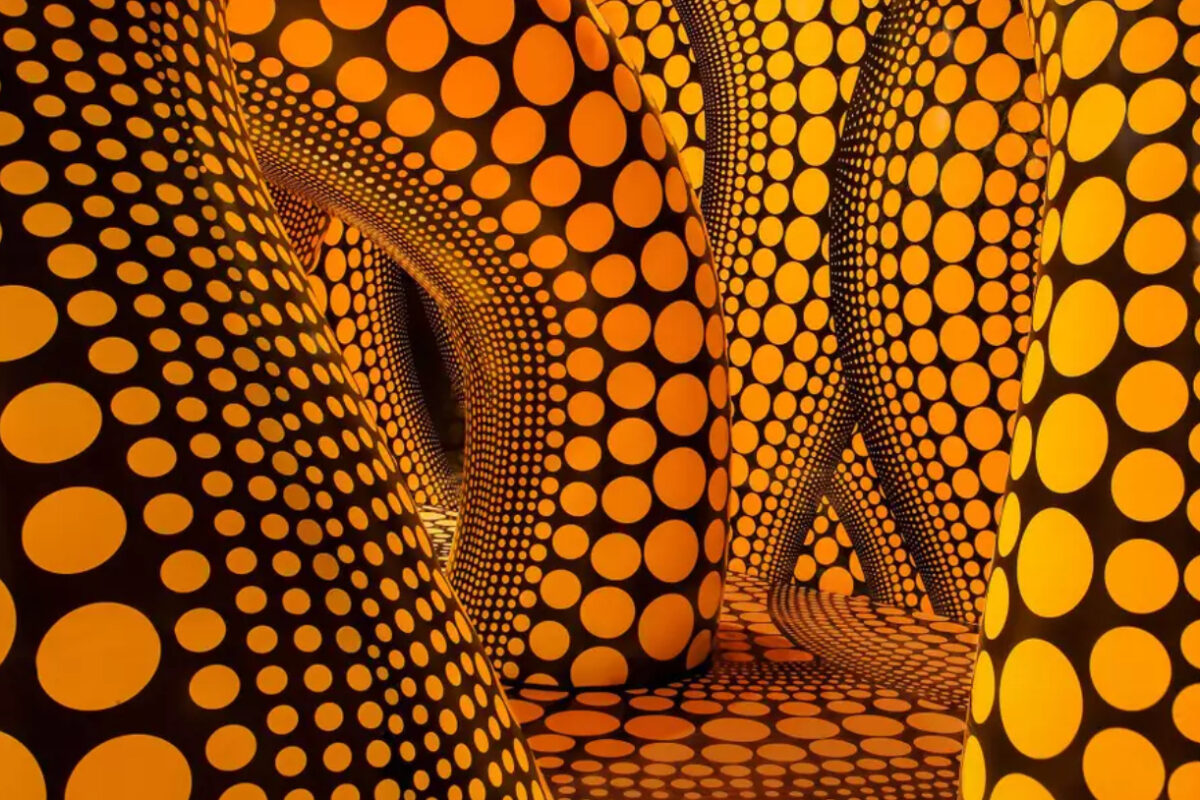

The Diverse Techniques of Yayoi Kusama

21 Aug 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Haring Decoded: The Symbolism of His Iconic Dog

12 Aug 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Happy Birthday Andy Warhol, The King of Pop Art

6 Aug 2025

Artists

The Psychology of Kusama

14 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

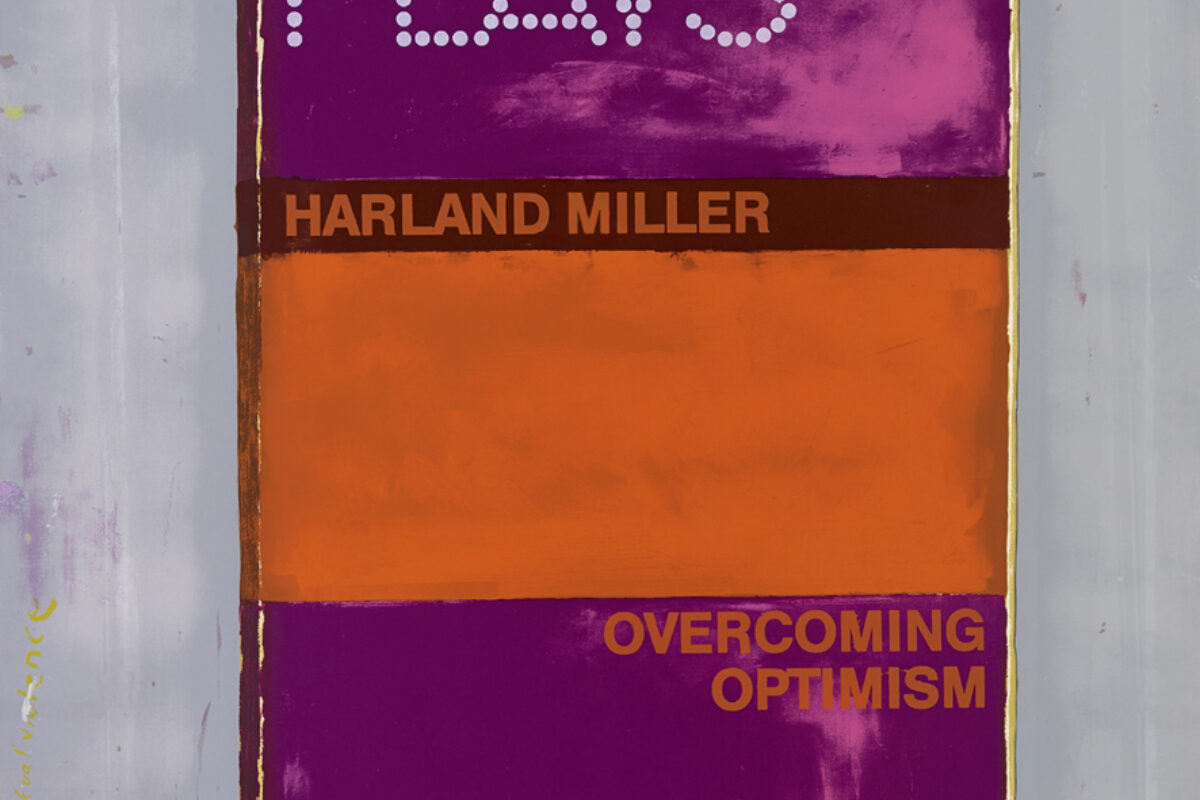

From Rothko to Ruscha: Unpacking Harland Miller’s Influences

10 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Decoded: David Shrigley

8 Jul 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Is David Hockney the Most Important Living Artist?

2 Jul 2025

Artists

Top 10 Selling Warhol Sets

15 Jun 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

David Hockney | 5 Groundbreaking Moments

23 Apr 2025 | 3 min read