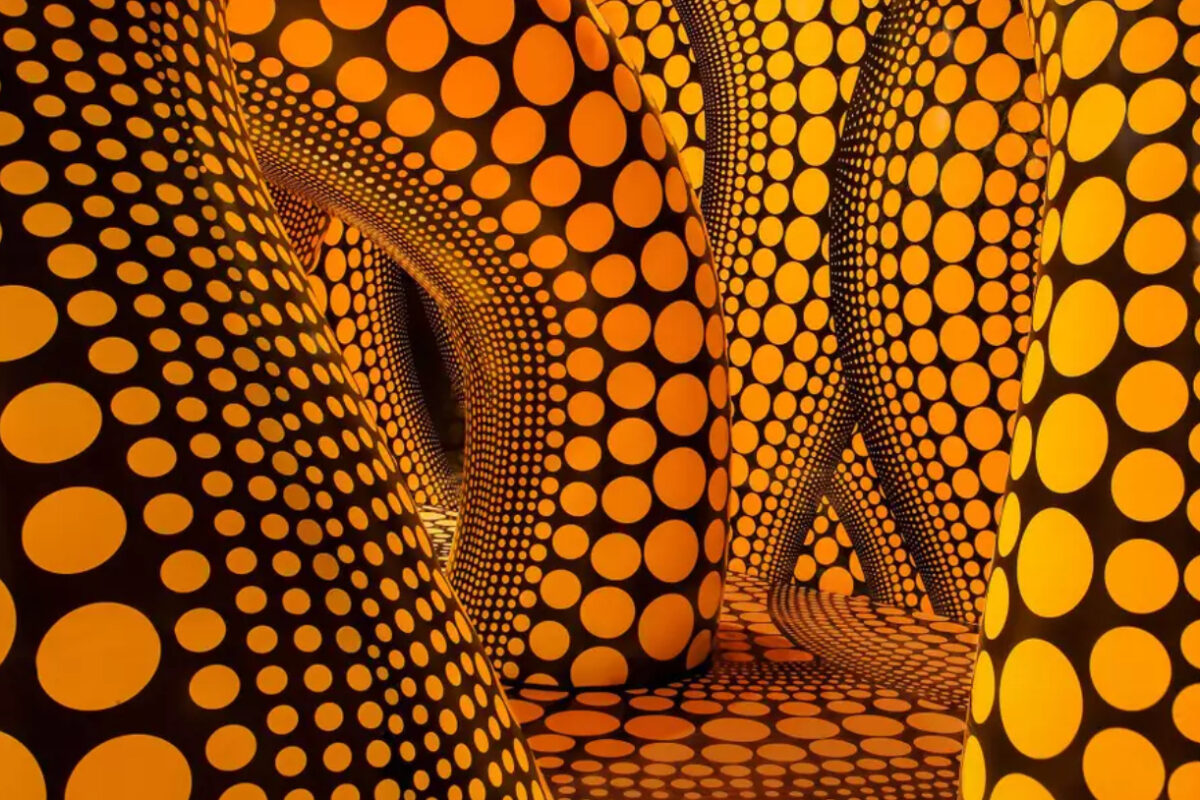

Kusama’s sold-out Infinity Mirror Rooms at the Tate Modern reveals the artist’s enduring appeal: she’s been making these immersive installations since 1965 but they continue to enchant audiences from Sydney to Aspen. It’s partly down to the transformative experience that they offer: visitors can disappear on a journey into her other-worlds (in Kusama parlance, “self-obliterate”), travelling straight into the inner workings of her mind.

If art is a window on the soul, then Kusama is the master. Although her career spans, and overlaps, with genres including Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism and Pop-Art, she defines her pieces as a way to convey her thoughts and mental health rather than any self-conscious attempt to join a movement. As she put it in the 2018 film Kusama: Infinity, “my work is based on developing my psychological problems into art.”

It could be argued that no other artist is as successful at transplanting the viewer so fully. Using motifs taken straight from her obsessions and hallucinations, she draws viewers into an alternative reality of endless lands conquered by repetitive shapes. “Accumulation is the result of my obsession, and that is the main theme in my art,” she explains, again in Kusama: Infinity.

It’s nothing, really

The focus of most of Kusama’s work is, as Akira Tatehata put it in his essay to accompany work shown in the 1993 Japan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, “consistently motivated by the desire for obliteration of the self.” Thus, her dots, infinity nets and infinity rooms repeat until they paper everything and there is nothing left of the artist (or the viewer).

Kusama’s popularity (she regularly tops charts of the yearly exhibition visitor numbers) may have detracted from the all-encompassing feel of the Infinity Mirror Room experience: due to high visitor numbers, you only get two minutes in each installation at the Tate, while some other galleries have granted ticket holders just 30 seconds. But they serve as a brilliant jumping off point for a deep-dive into Kusama’s unique world.

The artist’s I’m Here, But Nothing (2000) is a natural extension of the feelings sparked in her Infinity Mirror Rooms. Here, in a simple room set up for dinner, polka dots light every surface and the glittering magic that usually attracts such a loyal crowd of Instragrammers gives way to an uneasy emptiness. The piece is a direct interpretation of the hallucinations that Kusama has experienced since childhood: everything is covered in dots – and when you touch them, they cover you too until you become part of everything else. The scene is pretty, but by taking an ostensibly mundane set up and giving it an unexpected twist, Kusama invokes an uncomfortable alternative reality that’s akin to the other-realms of sci-fi TV series (such as the Upside Down of Stranger Things).

Kusama had been covering things in spots since her school days when she polka dotted some of her sketches. Her 1967 film Kusama’s Self-Obliteration is another claustrophobically evocative rendering of her off-focus reality. It begins with jerky, up-close images of infinity nets and moves on to trypophobia-inducing repetitions of penises and polka dots, before stop-motion footage of the artist in various scenes reveals creeping dots taking her over slowly until she disappears. Finally, an orgiastic scene of dot-smeared people gradually blur into nothingness. Set to an unnerving soundtrack of distant chanting, scattering piano and resonance, it’s haunting, other-worldly and disturbing – and redolent of the fears Kusama has faced since childhood.

Bad influence

In an interview with Tatehata for Phaidon’s Contemporary Artists series, Kusama described scenes of growing up, recounting “When I was a child, my mother did not know I was sick. So she hit me, smacked me, for she thought I was saying crazy things. She abused me so badly - nowadays, she would be put in jail. She would lock me in a storehouse, without any meals, for as long as half a day. She had no knowledge of children's mental illness.”

It was from this childhood that her themes were shaped. Her fear of sex, which reveals itself in armies of ‘phalluses’ enveloping chairs, boats and floors, stems from being tasked by her mother with spying on her father’s infidelity. Growing up on a seed farm and nursery, the young Kusama’s hallucinations included flowers that would speak to her. Thus, the blooms of Kusama’s adulthood (such as those from her Flowers That Bloom At Midnight sculptures) are rendered in bright colours and simple, childish shapes but they share the same otherness of her nets and dots. Outsized and looming, patterned over and over again, they seem almost predatory and invite the viewer to think again about flora as a perennially cheerful motif (in a review of a 2009 showing of these flowers at Gagosian for Art Forum, Catherine Taft noted “Kusama shrewdly demonstrates how visual treat might slide into subliminal threat.”

Much of the conversation surrounding Kusama focuses on the ebb and flow of her mental health and the fact that she lives voluntarily in an institution – but this narrative leaves no room for the artist’s consistent themes and ambition, exemplified by her move to New York in the 1960s, which was prompted by the stigma surrounding her diagnosis in Japan. While in New York, Kusama was relentlessly driven and sometimes idealistic, hoping to change the world view with her anti-war and pro-homosexual ‘happenings’, live events that often included elements of mass nudity.

Her work of the time – including Narcissus Garden, an unsanctioned installation piece at the 1966 Venice Biennale during which she sold mirror balls for $2 apiece – still involved her trademark large-scale repetition, but it also asked viewers to imagine alternate worlds, where art was not elitist and where sexuality was not criminalised. It also acted to keep her in a near-constant publicity storm, which Kusama allegedly saw as necessary in elevating her artist status.

Happy endings

In the time since Kusama returned to Japan and has undertaken therapy, some critics have viewed her art as becoming more optimistic. In 2020, she released a poem of hope in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic that seemed at odds with her previous written work: “In the midst of this historic menace, a brief burst of light points to the future. Let us joyfully sing this song of a splendid future”.

Her new work (shown this summer at galleries in London, New York and Tokyo) has also been described as joyful, though her motives remain ambiguous, and themes of obsession and obliteration remain. Whatever Kusama’s intention, there’s something therapeutic about her colourful canvases with their bobbing heads and Easter egg-like objects, rendered straight from her mind with no sketches or forward-planning. A mind able to conjure those without forethought – alongside stoutly tactile pumpkin sculptures and tiny universes in which we are nothing but stars in glittering nothingness – is definitely one worth celebrating.

Yayoi Kusama is one of six artists featured in our current Game Changers exhibition. You can see the works we have available from the artist in the viewing room below.