The 2022 sale of an Infinity Nets painting at Phillips achieved over £8 million, representing a significant milestone for female artists. In a market historically dominated by men, Kusama’s record-breaking auction result marked a transformative moment, highlighting the increasing recognition of women’s contributions to art. Beyond its remarkable value, the sale solidified Kusama’s standing in the art world, setting a new standard in her career trajectory.

'Untitled (Nets)' (1959), oil on canvas - £8,465,243 (Phillips, New York, 18th May 2022)

2. Kusama represented Japan at the Venice Biennale in 1966 and agin in 1993

Kusama’s succès de scandale reached its pinnacle at the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. Though not officially invited to exhibit, Kusama recounts in her autobiography that she secured both moral and financial backing from Lucio Fontana and permission from the Biennale Committee’s chairman to display 1,500 mass-produced silver plastic globes on the lawn outside the Italian Pavilion. These tightly arranged spheres created a mesmerizing reflective field, where the artist, visitors, surrounding architecture, and landscape were mirrored, distorted, and multiplied across their convex surfaces. The size of each sphere was similar to that of a fortune-teller’s crystal ball. When gazing into it, the viewer only saw his/her own reflection staring back, forcing a confrontation with one’s own vanity and ego.

During the opening week of the Biennale, Kusama displayed two signs at her installation reading, “NARCISSUS GARDEN, KUSAMA” and “YOUR NARCISSISM FOR SALE,” while dressed in a striking gold kimono with a silver sash. Acting as a street vendor, she sold the mirrored balls for two dollars each, distributing flyers featuring Herbert Read’s praise for her work. This performance highlighted the economic dynamics of art production and exhibition, though Biennale officials eventually stopped her sales. The installation, however, remained in place, gaining international media attention. The 1966 Narcissus Garden has since been interpreted as both a bold act of self-promotion and a critique of art’s commercialisation.

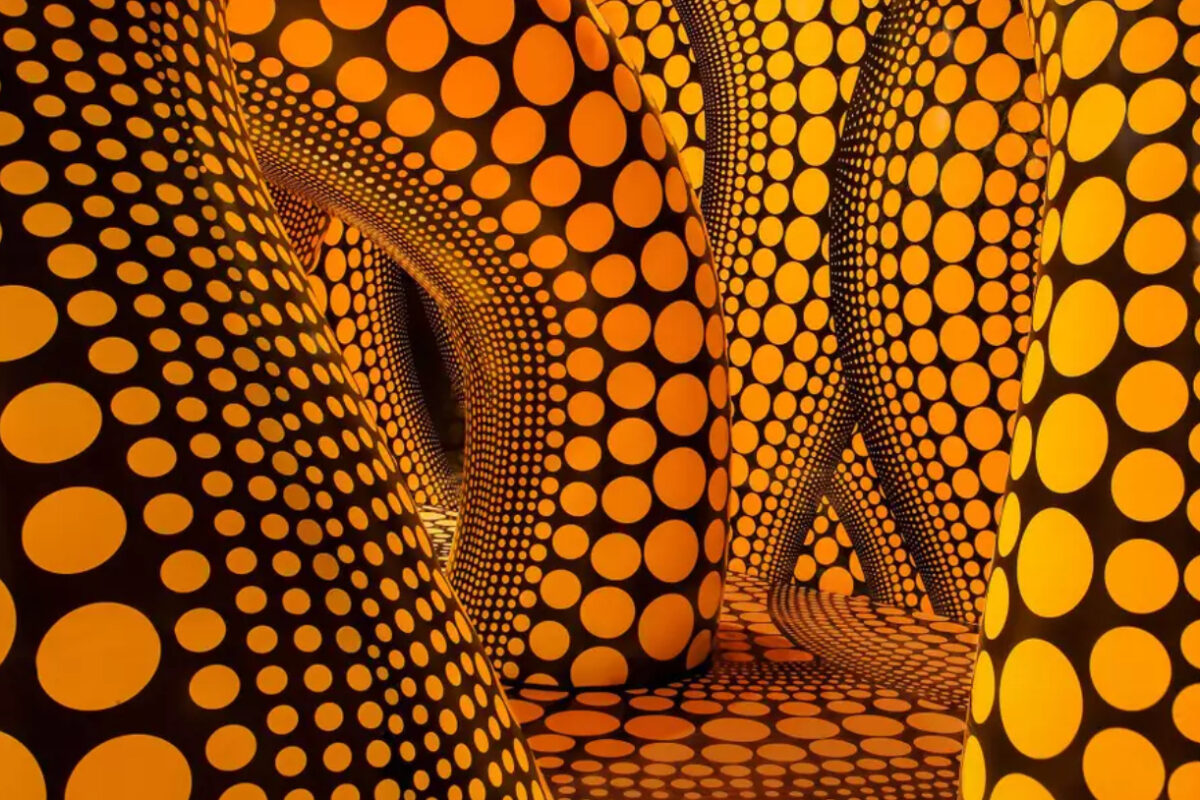

Kusama later went on to represent Japan at the Venice Biennale in 1993 with her Pumpkin Mirror Room. It was here that she re-introduced herself publicly to society after dealing with a mental breakdown years before. At this Venice Biennale, Kusama even handed out small pumpkins to attending visitors to take away.

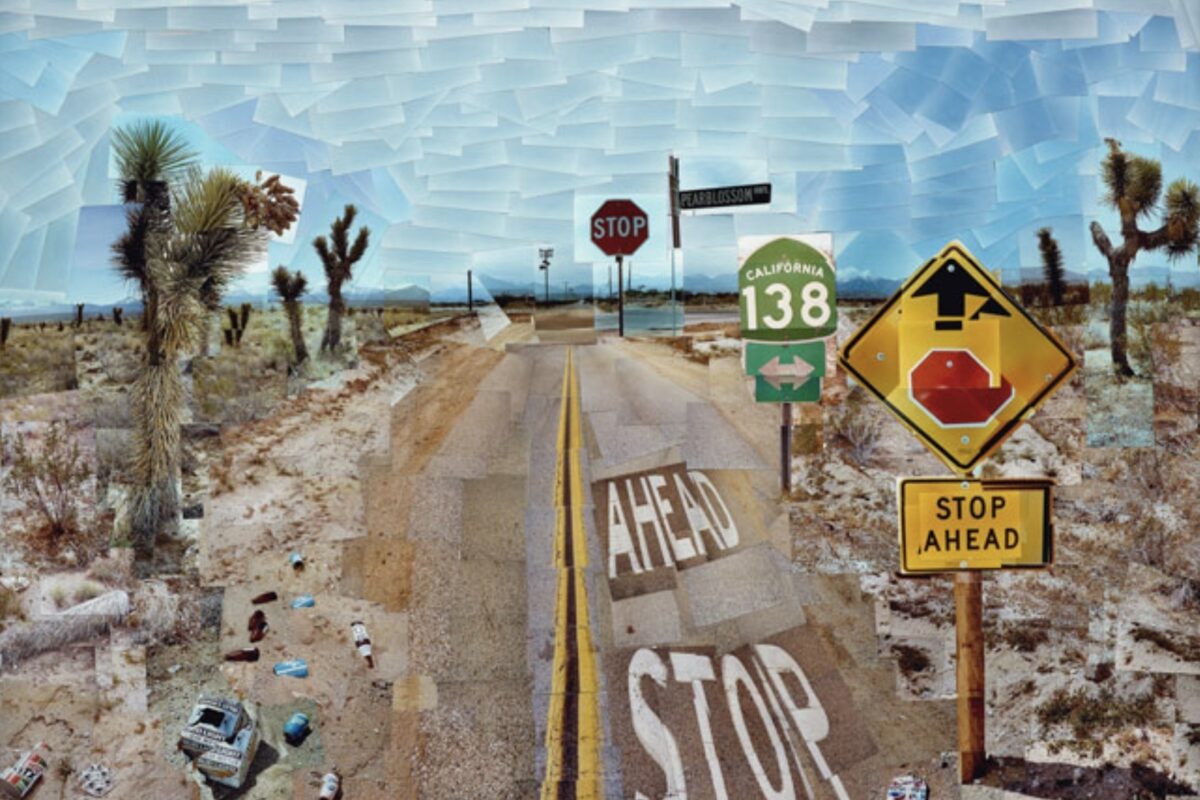

Yayoi Kusama Narcissus Garden, 1966, Installation view, 33rd Venice Biennale, 1966

Yayoi Kusama, Mirror Room (Pumpkin), 1991, Japanese Pavilion, Installation view, 45th Venice Biennale, 1993

Browse our available Kusama works

Click Here →3. Kusama studied traditional Japanese art

Kusama was raised in Matsumoto, and trained at the Kyoto City University of Arts for a year in a traditional Japanese painting style called nihonga.

She was inspired by American Abstract impressionism and moved to New York City in 1958 where she became a part of the New York avant-garde scene throughout the 1960s, especially in the pop-art movement.

“When I arrived in New York, action painting was the rage…I wanted to be completely detached from that and start a new art movement.”

-Yayoi Kusama

4. Kusama is best known for her infinity nets, polkadots and pumpkins

Yayoi Kusama produces art that ranges from paintings and sculptures to film and art installations. Her body of work is typically unified by her repetitive utilisation of dots, mirrors, and pumpkins.

Her fascination with pumpkins can be traced to her childhood. However, the pumpkin first appeared in Kusama’s artwork back in 1946 when she exhibited it in a traveling exposition in Matsumoto, her childhood town.

In the 1980s, Kusama began incorporating pumpkins in her dot motif drawings and paintings, as well as in prints and her environmentally conscious installation Mirror Room, which she created in 1991 for an exhibition at the Fuji Television Gallery and the Hara Museum in Tokyo.

Known in Japan as Kabocha, Pumpkins are positive images to Kusama because they represent a cheerful piece of her troubled childhood in Matsumoto. As a young girl, Kusama spent hours drawing pumpkins. To her, pumpkins are representative of stability, comfort, and modesty12. According to Kusama, she prefers to use pumpkins because not only are they attractive in both color and form, but they are also tender to the touch.

Yayoi Kusama’s patterns, including her Dots, are not only an aesthetic choice and motif, but they also serve a functional role for the artist. The repetitious painting of dots and other recurrent patterns, such as her infinity nets, is a means of coping with her experiences of hallucination, which, as a child, manifest in the form of terrifying visions of bright lights, spots, and other obliterating patterns.

Yayoi Kusama, Pumpkin (BSQ), 1998, Screenprint

5. Kusama had hallucinations

Kusama was born in 1929 into a well-off but dysfunctional seed merchant family in Nagano, Japan.

As a kid, her mother was physically abusive and often rebuked her for painting while her father was a known philanderer.

Largely shielded from the horrors of World War II, she was, as she has claimed, nevertheless scarred by her mother’s cruelty, her father’s infidelities, and her family’s discouragement of her interest in art making.

She started painting at the age of 10 when she began experiencing the visual and aural hallucinations that would often involve flashes of light, fields of flowers, dots, and pumpkins speaking to her. These would plague her, while also fuelling her creativity, for the rest of her life. She has maintained that her “artwork is an expression of my life, particularly of my mental disease.”

After many years in New York, in 1973, Kusama returned to Japan. Two years later, seeking treatment for her obsessive-compulsive neurosis, she entered a facility where she lives and works to this day. She continues to produce paintings and sculpture, and, in the 1980s, added poetry and fiction to her range of creative pursuits.

“My art originates from hallucinations only I can see. I translate the hallucinations and obsessional images that plague me into sculptures and paintings.”

—Yayoi Kusama

6. Kusama has voluntarily lived in a mental hospital since 1977

Since 1977, Kusama has chosen to live voluntarily in a psychiatric institution, with much of her work reflecting her struggles with obsessive thoughts and psychological trauma. Through her art, she seeks to convey her experiences, creating immersive installations filled with endless dots, intricate nets, and infinitely mirrored spaces that embody her unique vision.

Yayoi Kusama at work

7. Georgia O'Keefe was Kusama's friend and advisor

Kusama aspired to achieve the same renown as the American artists she admired in books. Among them, Georgia O’Keeffe stood out, inspiring her not only with her artwork but also with her success as a female artist. Motivated, Kusama decided to reach out to her via letter.

To Kusama’s surprise, O’Keeffe responded, warning Kusama of the difficulty of choosing such a path and advising Kusama to go to New York and show her work to anyone that was interested.

Although Kusama engaged in correspondence with O’Keeffe, the two didn’t develop the usual mentoring relationship. The two women knew and respected each other’s work but they kept their exchanges formal.

When Yayoi Kusama arrived in New York in 1958, O’Keeffe was living nearly 2000 miles further west, in New Mexico. Their relationship didn’t go further than a few correspondences and only one short meeting.

8. Andy Warhol was Kusama's friend but she also accused him of plagiarism

Kusama considered Andy Warhol a good friend, but she later accused him of stealing her ideas.

Kusama’s very first solo exhibition, “Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show” in 1963, showcased a rowboat sculpture made of phallic shapes, complete with two similarly adorned oars. The structure was photographed then replicated 999 times on the walls and ceilings. Warhol visited the exhibit and complimented Kusama on it, specifically commenting on the wallpaper and floor.

Years later, Warhol would debut his “Cow Wallpaper” installation in his April 1966 exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery, featuring one of his most recognizable and famous designs. The similarity wasn’t lost on the art community. However, Warhol credited an art dealer for the idea and did not mention Kusama.

Yayoi Kusama, New York, 1964

9. Kusama identifies as Asexual

Kusama developed an aversion to sex after her mother forced a young Kusama to spy on her father while with his lovers. She identifies as asexual, although her work often explores phallic forms and sexuality juxtaposed with elements of humour, like her soft sculptures in Phalli's Field Infinity Room.

“I began making penises in order to heal my feelings of disgust towards sex. Reproducing the objects, again and again, was my way of conquering the fear. It was a kind of self-therapy, to which I gave the name ‘Psychosomatic Art’.”

-Yayoi Kusama

10. Kusama is considered the most successful living female artist

At 94, Kusama is considered one of the most successful living female artists of all time. Her work at auction reflects it, often selling for above pre-sale estimates. In May of 2022, Phillips New York hosted their most successful auction in company history, with a new world auction record set for Kusama’s 1959 painting Untitled (Nets).

Internationally known for her extraordinary and otherworldly sculptures and installations, Kusama is also well-respected and widely collected as a painter. Anticipating the minimalist art movement, her white Infinity Nets reside in notable institutional collections, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Museum of Modern Art, New York, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Museum of Contemporary Art in Tokyo, among others.

Sign up for artist updates

Yayoi Kusama UpdatesMadeleine White

Senior Sales and Acquisitions

More editorials about Yayoi Kusama

Artists

The Diverse Techniques of Yayoi Kusama

21 Aug 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

The Psychology of Kusama

14 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Yayoi Kusama breaks records with the most successful exhibition in Australian history

17 Apr 2025

Artists

Yayoi Kusama at 96: A Celebration of the World's Best-Selling Female Artist

22 Mar 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Hang-Up's Top Exhibitions of 2024

23 Dec 2024 | 5 min read

Artists

10 Facts About Yayoi Kusama

30 Nov 2024 | 9 min read

Exhibitions

Yayoi Kusama at Victoria Miro

21 Oct 2024

Artists

Food Meets Art

7 Aug 2023 | 4 min read

Art Market

Art Market Insight | What, Why and How To Invest

19 Jul 2022

More from Artists

Artists

The Diverse Techniques of Yayoi Kusama

21 Aug 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Haring Decoded: The Symbolism of His Iconic Dog

12 Aug 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Happy Birthday Andy Warhol, The King of Pop Art

6 Aug 2025

Artists

The Psychology of Kusama

14 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

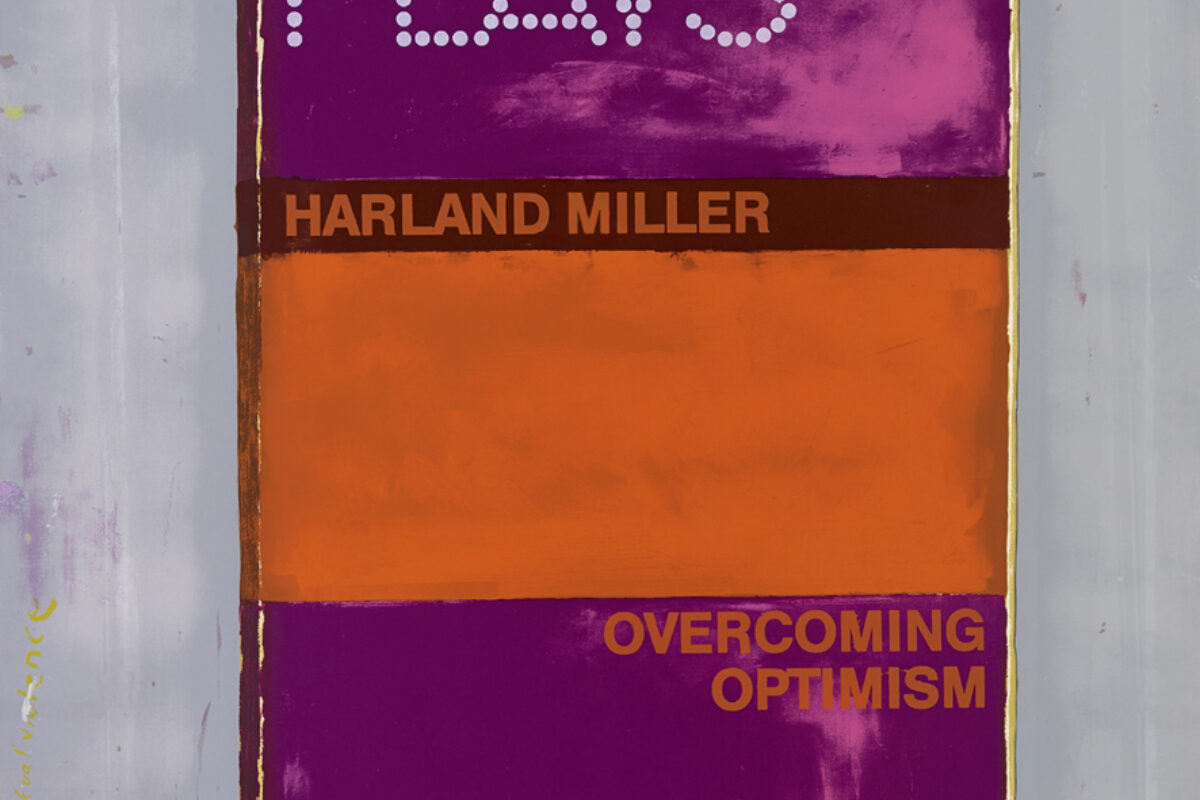

From Rothko to Ruscha: Unpacking Harland Miller’s Influences

10 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Decoded: David Shrigley

8 Jul 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Is David Hockney the Most Important Living Artist?

2 Jul 2025

Artists

Top 10 Selling Warhol Sets

15 Jun 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

David Hockney | 5 Groundbreaking Moments

23 Apr 2025 | 3 min read