Walk into one of the big galleries, and you might struggle to find jokes. For much of the 20th-century, art was considered high-brow and intellectual: there wasn’t much room for laughs. Even dadaists and surrealists such as René Magritte (most famous for his pipe that wasn’t a pipe) had more in mind than a quick chuckle when they created the movements: though individual works often contained humour, dadaism was a reaction to the atrocities of WWI and rigidity of thought within art, while surrealism was a reflection of a Freud-influenced alternative reality outside the conscious mind. (Salvador Dali was viewed as a bit of a joke by the surrealists themselves, however, due to his Hitler fixation and role as a brand ambassador for companies such as Alka-Seltzer).

By the mid 20th-century, the seriousness of abstract expressionism and minimalism had almost stamped out any hint of humour in art. However, by the 1980s things began to change. As Ralph Rugoff, then the Hayward Gallery’s director, told the Independent on the eve of its 2008 exhibition Laughing In A Foreign Language, "Humour's expanding role in contemporary art is a result of many factors, but perhaps above all it represents a kind of allergic reaction to the legacies of Modernism."

A Bit Of Light Relief

By the 1990s, humour was beginning to shake up the art establishment. Aware of its power to democratise art and widen its audience, a flurry of emerging artists used it to make work that was relatable rather than reverential. Gavin Turk’s 1991 piece Cave (which featured nothing but a blue plaque commemorating his working years) famously scored him a fail for his masters at the Royal College of Art – but it also garnered him membership to the YBAs, the most influential group of artists of the decade. Martin Creed, meanwhile, has always rebuffed claims that his works are funny, but even their names (Something on the left, just as you come in, not too high or low, for example, or A sheet of paper folded up and unfolded) raise a smile in anyone familiar with the stuffy confines of the traditional gallery setting. And David Shrigley’s unique brand of witticism made him immensely popular outside the usual realms of museums and galleries. Gaining a 2:2 from the Glasgow School of Art and subsequently drifting into unemployment, Shrigley won over his loyal audience with his trademark dry wit, which is evident in every work – from his taxidermy cat holding a placard that states “I’m dead” to his signature prints with slogans such as “wine: drink it quickly, before they take it away from you.”

Strange Times

Moving into the 21st-century, life was not the futuristic dream that many had envisaged. Instead, climate change, war and famine provided an apocalyptic backdrop to cultural endeavour. Art became a way to acknowledge the world’s man made horrors – without completely falling apart. Much of Banksy’s humour is a riff on our times: shopping trolleys in Monet’s pristine lake, doves of peace sporting bulletproof vests, and children pledging allegiance to a Tesco bag flag. The dark humour of his work encourages a pathos that news coverage often fails to produce. In a similar vein (but with more cute dogs and children), Magda Archer has added more and more political commentary to her work, attaching her signature witty slogans to cut-outs of the United Kingdom or questioning man-made destruction of the planet.

But though these artists deftly walk the line between humour and politics, Grayson Perry feels that others have struck the wrong chord. As a response to the increasing number of artists who use work to heighten political awareness, he has begun to poke fun at contemporaries who he feels exist in a left-wing echo chamber. For Selfie With Political Causes, Perry depicted himself riding a motorbike as of-the-moment discussion topics drifted around him. Speaking in The Guardian, he explained, “It’s a reaction to the way that politics has become very fashionable in art. I often want to go: ‘Wow, yes! I really agree with you, thanks for telling us about global warming, I’d never have guessed!’”

Photo Finish

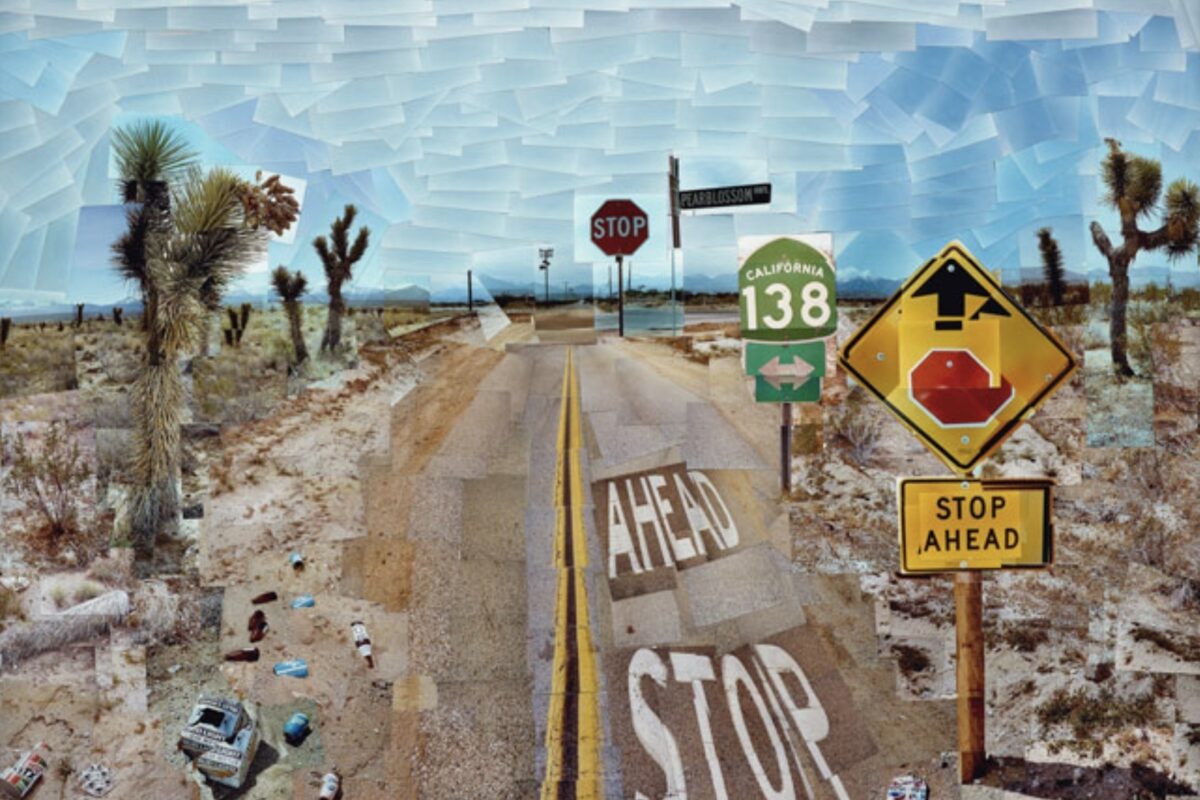

Arts increasing use of humour isn’t only led by the times, it’s also been influenced by the broadening of available mediums. Multimedia formats lend themselves to continuing narratives – a necessity for punchlines. Swiss artist Olaf Bruening addresses themes such as voyeuristic tourism and poverty through his films, which are simultaneously amusing and unnerving. As well as increasing the opportunity for story-making, digital methods have blurred the lines between art and entertainment: one of the best examples of this is fashion and advertising photographer David LaChapelle seamlessly moved into fine art in the first decade of this century, bringing his trademark surreal humour along with him.

Laughter Is the Best Medicine

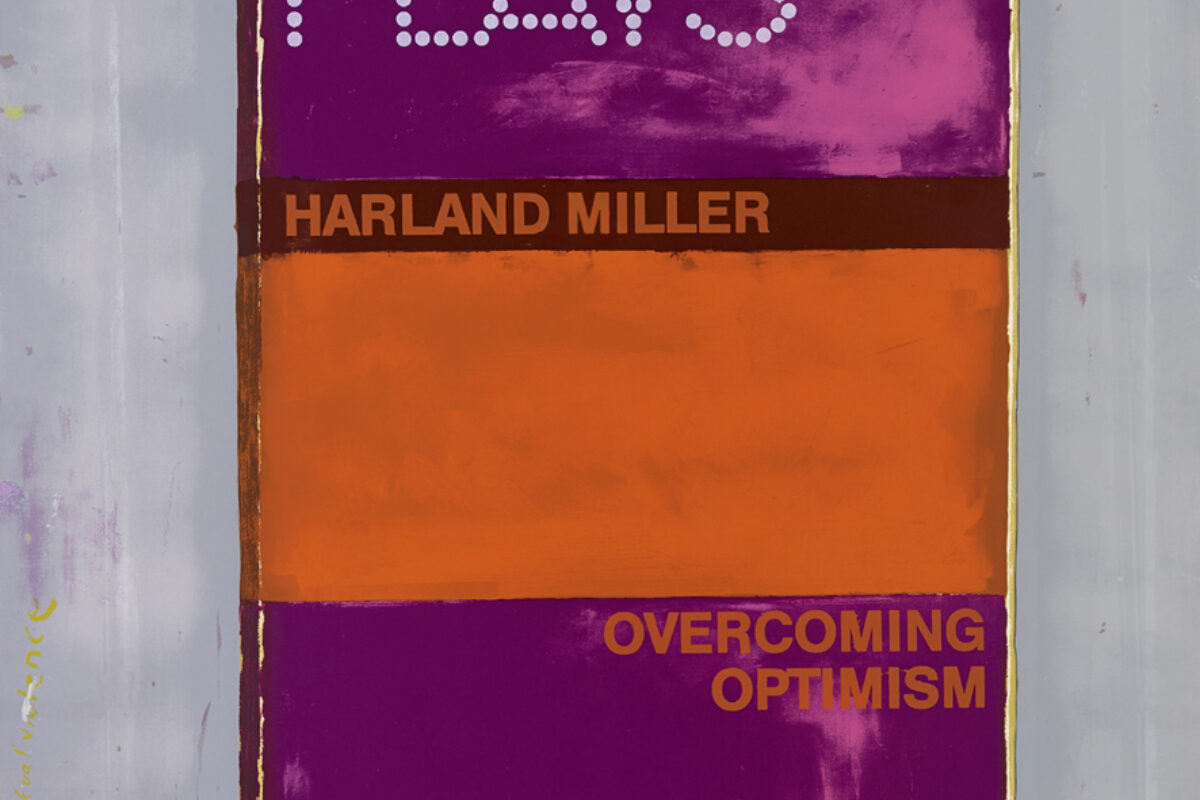

Away from the gallery setting, humorous pieces are a way to lift interiors and bring a daily smile to your face – which is in part why they prove so popular with many of our customers. Whether you favour the knowing, shouty wit of Tim Fishlock or Shrigley’s whimsical approach, we have all kinds of funny, just get in touch to find out more.