In our current exhibition, we explore the work of Patrick Hughes, known for his ‘reverspectives’ which create illusions of perception. Here, we take a look at how and why they work so well...

Hang-Up Gallery presents Patrick Hughes: The Perspective Paradox.

Simon Kallas

Stepping into the gallery space at Hang Up headquarters at the moment means embarking on a journey through the extraordinary 3D landscapes of Patrick Hughes. The artist terms his compelling reverspectives (in which perspective is seemingly reversed) as ‘full body illusions’, because they work best when you see them in the flesh and travel around them to get the full effect. The works are also at their most spectacular in large, well-lit spaces where they provide the main focus – so it’s worth coming down to our space to see them in all their splendour.

If you’ve never seen a reverspective, prepare to be amazed by the visual illusions they create. With pyramids and wedge shapes extending out of their surfaces to create their illusions, each work is an intricately-executed sculptural piece.

Tall Books, 2018, oil on board construction, at Hang-Up Gallery

Simon Kallas

What is ‘reverspective’?

Hughes explains the reverspective technique best himself:

"Reverspectives are three-dimensional paintings that, when viewed from the front, initially give the impression of viewing a painted flat surface that shows a perspective view. However, as soon as the viewer moves their head even slightly, the three-dimensional surface that supports the perspective view accentuates the depth of the image and accelerates the shifting perspective far more than the brain normally allows. This provides a powerful and often disorienting impression of depth and movement."

The technique sets Hughes’s work apart from the linear perspective of traditional two-dimensional paintings, where lines converge at a single point to create the illusion of depth.

Hughes’s first reverspective was the simple ‘Sticking Out Room’, executed in 1964, which shows an empty, wall-papered living room. Later though, the artist’s subject matter became influenced by the landscapes of the surrealist movement, and his use of other-worldly spaces (where famous paintings hang in empty galleries that are open to the skies or Venetian palaces sit on desolate canals, for example) heighten the feeling of having stumbled across a parallel world, in which everything is similar but somehow different.

In addition, the pyramid and wedge-shaped protrusions, shadows and lines that form the structure of Hughes’s illusions have become more complex in the last three decades, allowing more of his landscapes to come to the foreground or retract and thereby creating more impressive tricks of perception.

Details of Caring Haring, 2021, oil on board construction.

Simon Kallas

Weird science

Reverspective is an abbreviation of reverse and perspective, and Hughes’s works are so labelled because the views are painted in reverse (as Hughes puts it, “the bits that stick furthest out from the painting are painted with the most distant part of the scene”).

The reverspective idea is unique (although it has spawned numerous copycats), and because the technique relies on images being righted by the brain upon viewing, it has captured the attention of psychologists preoccupied with tricks of the eye and the mind, notably Nicholas J Wade (currently an emeritus professor at the University of Dundee) and Thomas V Papathomas (Associate Director of the Laboratory of Vision Research at Rutgers) who have both collaborated with Hughes on academic papers.

In the 2019 article Hughes’s Reverspectives, Papathomas explains the illusions that come together in the artist’s most recent works, saying: “different parts of the same planar surface are painted with conflicting perspective cues such that some parts appear to belong to a convex object while other parts appear to be lying inside of concave spaces. The end result is that these parts appear to move in different directions, which is a physical impossibility, since they are parts of the same planar surface.” This trick of the eye has proved fascinating for those involved in visual research, and Hughes continues to be the subject of many academic texts focused on perception.

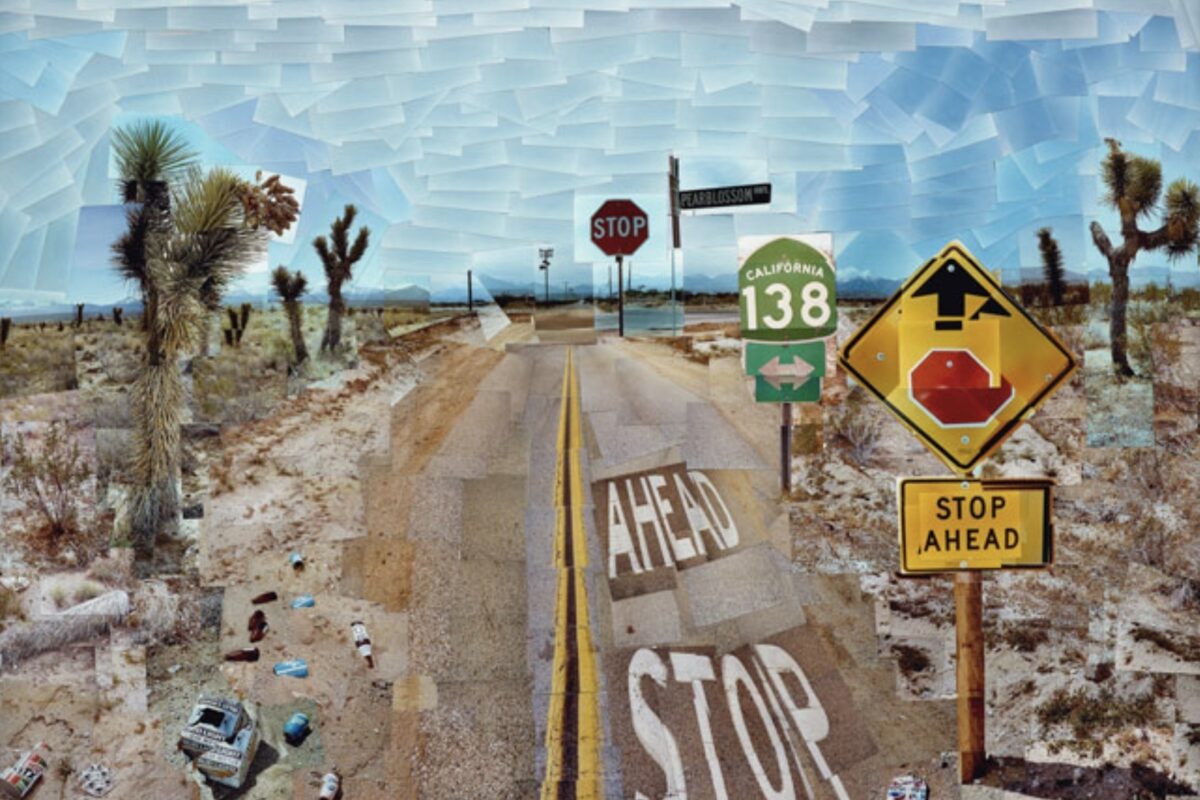

The Writing on the Wall, Cuboids and All Over at Hang-Up Gallery.

Simon Kallas

At home

The reasons that we see Hughes’s work in the way we do are complicated and manyfold. Luckily, there’s no need to understand the science behind reverspectives in order to enjoy their effects. For collectors, Hughes’s works are a pleasure to hang, creating arresting visual interest in any room through a combination of engaging, familiar subject matter and mind-bending visual trickery. Get in touch with us to find out which works from our exhibition are available or to book an appointment to look around.

Viewing Room Public

Patrick Hughes: The Perspective Paradox

Opens:

26 Oct 2021

Celebrating sixty-years of reverspective

View ArtworksMore editorials about Patrick Hughes

Artists

Artist Influences

22 May 2023 | 3 min read

Artists

The Perspective Paradox | In Conversation with Patrick Hughes

15 Dec 2021

Artists

Weird Science: Reverspective

15 Nov 2021

Artists

The Perspective Paradox | A Look at the Private View

2 Nov 2021

Artists

Introducing | Patrick Hughes: The Perspective Paradox

6 Oct 2021

Artists

Artists to Watch | 2021

3 Jan 2021

Artists

Five Questions With | Patrick Hughes

12 Nov 2020

More from Artists

Artists

The Psychology of Kusama

14 Jul 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Decoded: David Shrigley

8 Jul 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

Is David Hockney the Most Important Living Artist?

2 Jul 2025

Artists

Top 10 Selling Warhol Sets

15 Jun 2025 | 2 min read

Artists

David Hockney | 5 Groundbreaking Moments

23 Apr 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Yayoi Kusama breaks records with the most successful exhibition in Australian history

17 Apr 2025

Artists

An Interview With Mark Vessey

9 Apr 2025 | 7 min read

Artists

Yayoi Kusama at 96: A Celebration of the World's Best-Selling Female Artist

22 Mar 2025 | 3 min read

Artists

Super Woman | Why Tracey Emin standing up to the haters is good for you too

8 Mar 2025